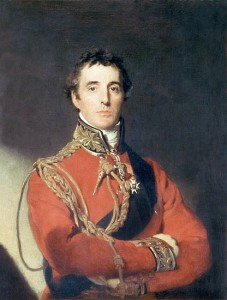

“My my, at Waterloo Napoleon did surrender” are the opening lines of Abba’s winning song at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1974. Worryingly a recent survey by the National Army Museum found that most young people had never heard of the Battle of Waterloo. Most only identified it as a pop song or railway station. The survey also found that two thirds of people did not know that the Battle was fought exactly 200 years ago (June 18th, 1815), and even half of those who had heard of the Battle did not know that the Duke of Wellington commanded the allied side against Napoleon.

The Battle was not actually fought at Waterloo, but at a tiny village called Mt. St. Jean. Today the battlefield is marked by a rather ugly lion monument. It got its name because

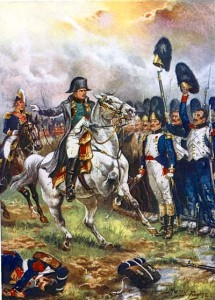

Wellington wrote his famous despatch describing his victory that night at the village of Waterloo, a few miles away. It was the culmination of the famous “Hundred Days”. Napoleon had escaped from his exile in Elba after his defeat in 1814 and returned in triumph to Paris to reclaim his throne. The allies, who had spent more than 10 years fighting the French, were in no mood to listen to his claim he wanted peace and at once declared war on France and mustered their armies. From that moment Napoleon’s gamble was lost. He did wonders rebuilding his army in a few weeks and then moving it with speed and secrecy to the Belgian border. Here were the nearest of Napoleon’s enemies – the Prussians led by Field-Marshal Blucher and an odd mixture of an army led by the British Duke of Wellington. In fact barely half of his army were British. The rest were made up of various German and Dutch contingents. The Dutch in particular were both inexperienced and unreliable.

Napoleon caught his enemies by surprise (as Wellington freely admitted). He was able to separate the two armies and thought he had defeated both of them at the separate battles of Quatre Bras and Ligny (June 16). Napoleon imagined his enemies fleeing in panic – the British North to the Channel, the Prussians East back home. In reality both retreated north and kept in touch with each other. Neither had been beaten as heavily as Napoleon thought. But even if Napoleon had been right and that he had won decisively, it would only have delayed his final defeat. The vast armies of Russia and Austria would soon be ready to join the campaign and it is hard to see how Napoleon could have held on for long.

As it was, Napoleon was still confident when he caught up with the retreating British on June 18th. Neither Commander showed exceptional skill at this most famous of battles. Napoleon launched a series of frontal assaults which failed to break the British lines. Napoleon actually left most of the fighting to some of his Generals and seemed tired. Wellington showed more skill, and knew if he could hold on long enough, the Prussians would arrive to help him, but he too made mistakes. In particular he seems to have forgotten about a substantial force he had left a few miles to the West. He never summoned these reinforcements and they never fired a shot.

When the Prussians did arrive, it was Napoleon’s turn to be caught by surprise – he had assumed they were dozens of miles away and in full retreat. The French army collapsed and Napoleon’s gamble had totally failed.

The battle, which finally ended the Napoleonic Wars, was bloody and brutal. 200,000 men

took part along with 60,000 horses and more than 500 cannon. Up to 50,000 men were killed in that one day – a figure comparable to the Battle of the Somme. Wounded soldiers had limbs amputated without anaesthetics, and as soon as the Battle was over, local civilians rushed to rob the dead of their boots, clothes and even their teeth (which could be made into dentures). Glorious it was not.

The Battle had been, as Wellington conceded, “a close run thing”. It was not won by superior skill, character or weapons by the British. Instead it was a killing field which was decided by the superior numbers of the allies and Napoleon’s blunder in thinking the Prussians were finished. Abba were wrong to say Napoleon surrendered at Waterloo (in fact he held on for another 3 weeks before accepting the game was up) – but it’s still a good song.