October 2016 marked the 950th Anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, one of the best known dates and events in English History. Yet whilst a huge amount has been written about the Battle- Google alone has 13 Million links- there is much that still remains argued about, including the causes of the war, the reason Harold lost, how he died and the importance of the battle.

October 2016 marked the 950th Anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, one of the best known dates and events in English History. Yet whilst a huge amount has been written about the Battle- Google alone has 13 Million links- there is much that still remains argued about, including the causes of the war, the reason Harold lost, how he died and the importance of the battle.

The problem began with the previous King, Edward the Confessor. Exceptionally pious even for the time- hence his nickname- he failed in his primary duty as King by not having a son, leaving the succession open to argument. When Edward died in January 1066, three men claimed to be the rightful King. They were King Harald of Norway, Duke William of Normandy and Harold, Earl of Wessex. Harold’s claim was not strong- he was married to Edward’s sister- but he was English and the only one actually in the country when Edward died, so he was very quickly crowned King with the approval of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Witan (the Council of Nobles).

Harold knew from the start he would be challenged by the other two claimants. William in particular, a ruthless experienced leader had a better claim to the throne. A few years previously both Edward and Harold had agreed he should be the next King, although Harold claimed he was forced to swear the oath of loyalty, so it did not count. William, keen to get control of a country much larger and wealthier than his own, at once started to build up his army.

William was both skilful and lucky in his preparations. He showed real skill in persuading Pope Alexander II to support his campaign. In an age where religion was the most important thing in people’s lives, getting the Pope to declare William to be the rightful King was crucial, enabling him to recruit large numbers of men who were now fighting a religious Crusade as well as in the hope of land and loot.

He was lucky with the weather. By the summer his army and navy were assembled, but the winds blew the wrong way for weeks on end and William was stuck in Normandy. Had he landed at that time as he planned, he would probably have been defeated. As it was, he was unable to land until 28th September- and Harold’s army was nowhere in sight. The English army had rushed to Yorkshire to crush the Norwegian invasion. This gave William time to rest his men, start building a simple castle at Hastings and seize supplies from local villages.

Harold’s decision to rush back to Hastings with his exhausted and under-strength army has been much debated. If he had waited patiently, building up his army whilst William was stuck in a hostile country with winter approaching, Harold might have won the war. On the other hand, having already won one total victory against the Norwegians and with a battle-hardened army, he was confident of a second win- and the English might not have understood if he not challenged William at once.

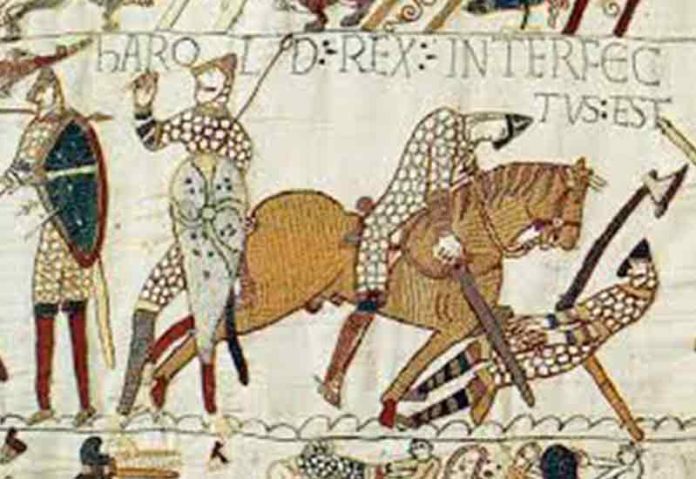

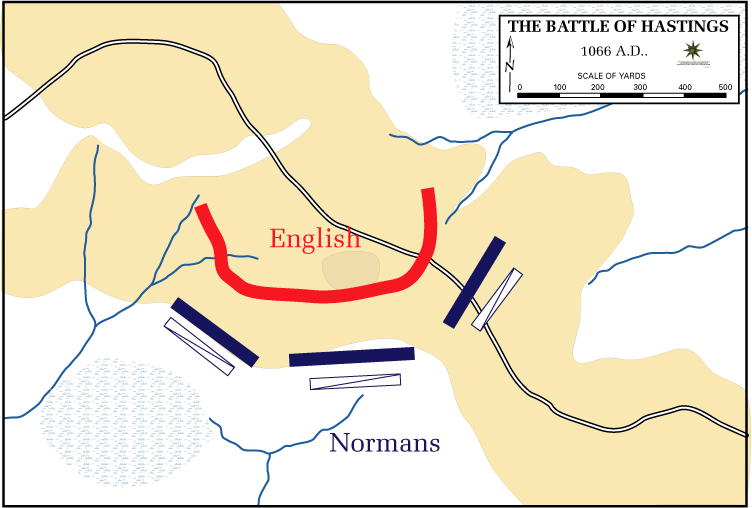

The Battle took place on 14th October, and a Norman victory was always likely. Not only was William’s army rested, but it was much larger than Harold’s and had the archers and cavalry that Harold lacked. Nevertheless it was a hard fight lasting several hours before Harold was killed and the English army collapsed.

But how did Harold die? The problem is that the vital section of the Bayeux Tapestry (pictured) can be interpreted two ways. Is Harold the man shot in the eye, or the one being cut down by a horseman? We simply do not know

The death of Harold meant William was the last King standing in 1066. He quickly captured London and was crowned on Christmas Day, making 1066 “The Year of Three Kings”. However revolts against Norman rule continued for several more years, and it was these, rather than the first battle, that persuaded William to remove nearly all the English nobles and clergy and instead impose Norman nobles in their stone castles. With the Normans came the Feudal system, the French language and laws, and England found itself part of Europe.

In the end 1066 was about much more than just a change of King. It deserves its place as one of the most important dates in English History